Yuan devalued by 2% to boost the Chinese Economy

11/08/2015

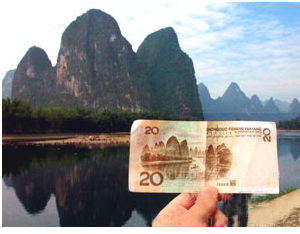

On Monday, August 10th 2015, China’s decision to devaluate the Yuan by 2% became public. The reasons for …

L’histoire derrière le Yuan

03/06/2014

Généralités : Chaque jour en Chine, nous prenons nos sacs pour acheter nos provisions, notre eau et nos …

Max on the Influences and Development of the Chinese Language

18/07/2013

Note: This topic is still controversial academically The Chinese language as we know it not only has different …